In Focus

Nov 7, 2025

- Literature and Human Sciences

How the Retro Boom for the Showa Era in Japan is Shaping Urban Tourism

Associate Professor Keita Amano

Graduate School of Literature and Human Sciences, Department of Cultural Management

The year 2025 marks the 100th anniversary of the start of the Showa era. Recently, interest in the culture of the era has grown, and ‘Showa retro’ has become popular among young people and foreign tourists. Osaka Metropolitan University caught up with Professor Keita Amano to ask him about the enduring appeal of the era and his ideas about appreciating the recent past as a form of ‘retro tourism.’ Amano is actively researching the background of the boom, its evolution, and possible future.

The ‘light exoticism’ behind the retro boom

Just the mention of the word Showa brings to mind classic-style coffee shops with their soft leather coaches, cheap restaurants serving Japanized Chinese dishes, and public bathhouses with colorful interiors. The era was a time when the latest technology was cassette tapes, analog records, and film cameras. Yet despite our familiarity with these things and the culture that existed at the time, it is hard to pin down exactly what ‘Showa retro’ includes.

“The Showa era lasted for approximately 63 years, from 1925 to 1988, which is a relatively long period of time. So, the appearance of the society at that time varies depending on which period you focus on, as well as greatly depending on the individual,” Amano said. “The term ‘retro’ in this sense, often has a nostalgic feeling of a period representing ‘the good old days.’ That rose-tinted way of looking at the past is part of the appeal of ‘Showa retro.’”

According to Professor Amano, the concept of Showa retro, in the context of tourism, began gaining popularity as a commercial opportunity in the early 1990s. During this period, even modern developments embraced a nostalgic aesthetic. For example, Takimi Koji, a retro-style restaurant alley in the basement of Umeda Sky Building in Osaka City (built in 1993), and the Shin-Yokohama Ramen Museum, a food theme park in Yokohama City (opened in 1994), were both designed to evoke the charm of the Showa era.

After the 90s, a bigger boom came in the 2000s with the success of movies that were based on the Showa era of the 1950s to the early 1970s. The trend started with the drama ALWAYS: Sunset on Third Street (2005). This was followed by more child-friendly offerings like Crayon Shin-chan: The Storm Called: The Adult Empire Strikes Back (2001), which found the lovable animated character saving adults who were brainwashed into regressing to their Showa-era personalities.

Both these movies were huge hits, increasing their viewers’ awareness of the lifestyle and culture of that era. Riding this wave of popularity, exhibitions and events themed around the Showa era were held across Japan. Even after the 2010s, museums and dining districts directly inspired by the Showa era started appearing.

Although the retro boom has continued unabated, Professor Amano stresses that what era is considered retro and what everyone is interested about in that era is constantly changing:

“The reason why ALWAYS and Crayon Shin-chan’s movie were hits was that many people who saw the movies felt nostalgic for the Showa era, especially the 1950s, 60s, and early 70s. Many viewers felt that those were the good old days,” he said. “However, the recent focus on ‘retro’ has started to include later eras, like the Showa period of the early 1970s and later. There is a trend among younger generations in Japan and even among foreign visitors —who, of course, did not live through that era— to find the culture of the late Showa period and early Heisei period appealing. Often, they are not necessarily nostalgic for the past but are interested in these eras as a ‘new culture’ they have never experienced before.”

Professor Amano explains that behind this phenomenon lies a desire for what he terms ‘light exoticism.’ In this case, ‘exoticism’ includes meanings of a desire to experience a place that feels foreign or has a foreign atmosphere, whereas ‘light’ suggests that this can be experienced in a casual, easily accessible way. In ‘light exoticism,’ visitors get a hint of something different, but at the same time familiar. However, is this really a fair description of the appeal of Showa retro?

“The fundamental essence of tourism could be thought of as experiencing cultures and landscapes that differ from those experienced in your everyday life,” Amano said. “In cases of light exoticism, the focus is not on the atmosphere of a foreign country or buildings that remain from the Edo period, but rather the feeling and culture of the recent past. As an example, it is generally hard to get people these days to be interested in seeing toys from the ancient Kamakura period (1185–1333 AD), but if a young person playing on a Nintendo Switch were to see something from the more recent past, like the original Nintendo Entertainment System (1983), they might think, ‘So that's how it was back then,’ and enjoy the differences between what they have and the original version. In this sense, the current retro boom can be seen as arising from a growing desire to experience the recent past. The visitor can enjoy experiencing a familiar culture closely connected to their everyday life but in a different way.”

Retro tourism as a new tourist experience in cities

Recently, the concept of “retro” has become established as an aspect of tourism, but how has urban tourism changed over time?

“In the field of tourism research, cities were not previously considered to be tourist destinations. It was commonly held that most people in urban areas travel to rural areas to experience the nature and history of those regions. However, in reality, just as we travel to Paris or London when we visit Europe from Japan, many foreign tourists coming to Japan concentrate on the urban areas of Tokyo and Osaka. This has informed research as well. Since the 2000s, cities have begun to be recognized as places that play a very important role, albeit to a limited extent.”

Modern cities are often thought of as having similar landscapes, basically being nothing but a series of tall buildings. However, as Professor Amano points out: “Tourists themselves discover the unique characteristics and non-uniform aspects of each city.”

“Tokyo's Shinjuku Golden Gai, which originated in the black markets of the postwar period, and Osaka's Tobita Hondori Shopping Street, which used to be a neighborhood for day laborers, are now popular among foreign tourists as places where they can experience Japan's unique lifestyle and culture,” he said. “On top of this, we are recently seeing the phenomenon of foreign visitors having an interest in areas with vibrant nostalgic subcultures like the retro gaming scenes of Akihabara in Tokyo and Nipponbashi in Osaka.”

One form of urban tourism that is emerging as a new kind of tourism in such cities is ‘retro tourism,’ which Professor Amano defines as “tourism practices that utilize the streetscapes and culture of the recent past as tourist attractions.”

“The retro tourism trend did not start because countries or local governments promoted it on a large scale or its popularity piggybacked on some event,” he said. “Instead, it is based on tourists themselves discovering and enjoying the charm of a city. Although movies inspired by the Showa era, especially ALWAYS, had a role in sparking the retro boom, recently it has been enhanced by young people and foreign tourists discovering interesting things and sharing them on social media.”

Retro as a concept opens up channels of communication

Retro tourism usually develops naturally, but it plays a major role in revitalizing regional cities and shopping districts and bringing new tourism resources to an area. For example, Bungotakada City, Oita Prefecture, began a project in 2001 to revitalize the shopping district by creating a Bungotakada Showa no Machi (Bungotakada Showa Town) in a corner of the city center that was based on the Showa period of the 1950s to 60s. At its peak in 2011, it attracted over 400,000 visitors annually and won numerous regional development and tourism awards.

Professor Amano believes that there are two major benefits to utilizing retro tourism in urban development:

“First of all, retro tourism does not incur high costs. Traditional shopping districts that have that old-fashioned atmosphere can be used as tourist attractions as they are, reducing the costs compared to large-scale redevelopment projects,” he explained. “Second, such tourism opens up channels of communication between local residents and tourists. For example, in Bungotakada City, shops display rare tools passed down through generations or tools that were used in traditional industries in their storefronts. These are called ‘one shop, one treasure.’ These items can serve as a catalyst for conversation and interaction between shop owners and tourists. As a result, channels of communication between people are opened up through the common theme of memories of the recent past.”

Showa-era Town in Bungotakada City (Oita Prefecture) / Source: Oita Prefecture Tourism Information Official Website https://www.visit-oita.jp/)

In addition to Bungotakada City, there are many other examples of town development utilizing Showa retro culture, such as the Kurayoshi Retro Museum in Kurayoshi City, Tottori Prefecture, which showcases Showa-era toys and tools; and the Tamashima district in Kurashiki City, Okayama Prefecture, which contains buildings from the era.

What is necessary to maintain and develop these tourist destinations so that they do not end up as a passing fad?

“Tourism is highly subject to trends, so it is necessary to constantly renew and revitalize attractions, much like how Universal Studios Japan continues to create new attractions. This is different in retro tourism, as it aims to preserve the unchanged, traditional aspects of a place. Another important facet is making it so that fans feel attached to certain places or things. This way, for example, when the owner of a café becomes elderly and decides to close the shop, the shop can be revived in a different form by people who have been loyal customers or feel a strong connection to the place. I believe that fostering communication with these fans is essential for ensuring that the legacy is passed on to future generations.”

There are two sides to this that need to be balanced: on the one hand, the need for renewal and on the other, the importance of preserving the traditional appearance. “It is precisely because of these two sides that cities are so interesting,” Professor Amano said with a smile.

“Cities are often compared to mosaics, meaning they contain disparate and diverse elements. In many cities, the atmosphere can change dramatically just by crossing a single street. I believe it is important to create cities that retain this mosaic-like quality. I think the variety of ways to enjoy urban tourism will continue to increase in the future, and I would like to be involved in proposing and developing new ways to enjoy cities from perspectives that have never been considered before.”

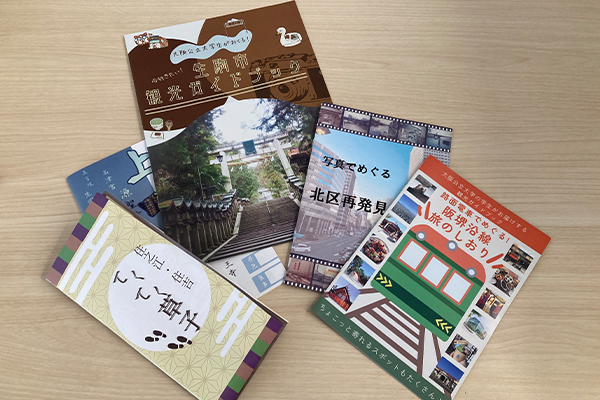

A guidebook created with students as part of the curriculum

A guidebook created with students as part of the curriculum

Finally, we learned about ways to enjoy urban tourism that busy businesspeople can incorporate into their daily lives.

“Why not take a closer look at things that catch your eye on your daily commute? Whenever you wonder what something is, go and check it out and you may discover new insights into the history and charm of the area. An old creek may have been a river at one time, or an interesting old road may have been a highway in the Edo period. It's fun to explore a city and unravel an area’s mysteries. Another recommendation is to find your favorite spots in each city. Even in a place you casually walk through during a business trip, looking a bit further and discovering an interesting location or an attractive place might spark a new appreciation of that city.”

Researcher’s details

Associate Professor Keita Amano

Graduate School of Literature and Human Sciences, Department of Cultural Management

Profile: PhD (Sociology). Master’s degree and doctorate from the Department of Sociology, Faculty of Letters, at Chuo University. Previous positions as a full-time lecturer at Shizuoka Eiwa University and associate professor at Tokyo International University, before entering Osaka City University (now OMU) as an associate professor. Research interests include tourism studies and urban sociocultural theory, with a primary focus on interpreting tourism in urban contexts, contemporary tourism styles, and the relationship between media and tourism behavior from sociological and cultural perspectives.

SDGs